Caroline Morris

Catalog Number: 2014.fic.135

“A major emergency affecting a large number of people may occur anytime and anywhere. It may be a peacetime disaster such as a tornado, flood, fire, blizzard, or earthquake. It could be an enemy attack on the United States. … If you and your family take action as recommended in this plan, you will have maximum chances for survival.”

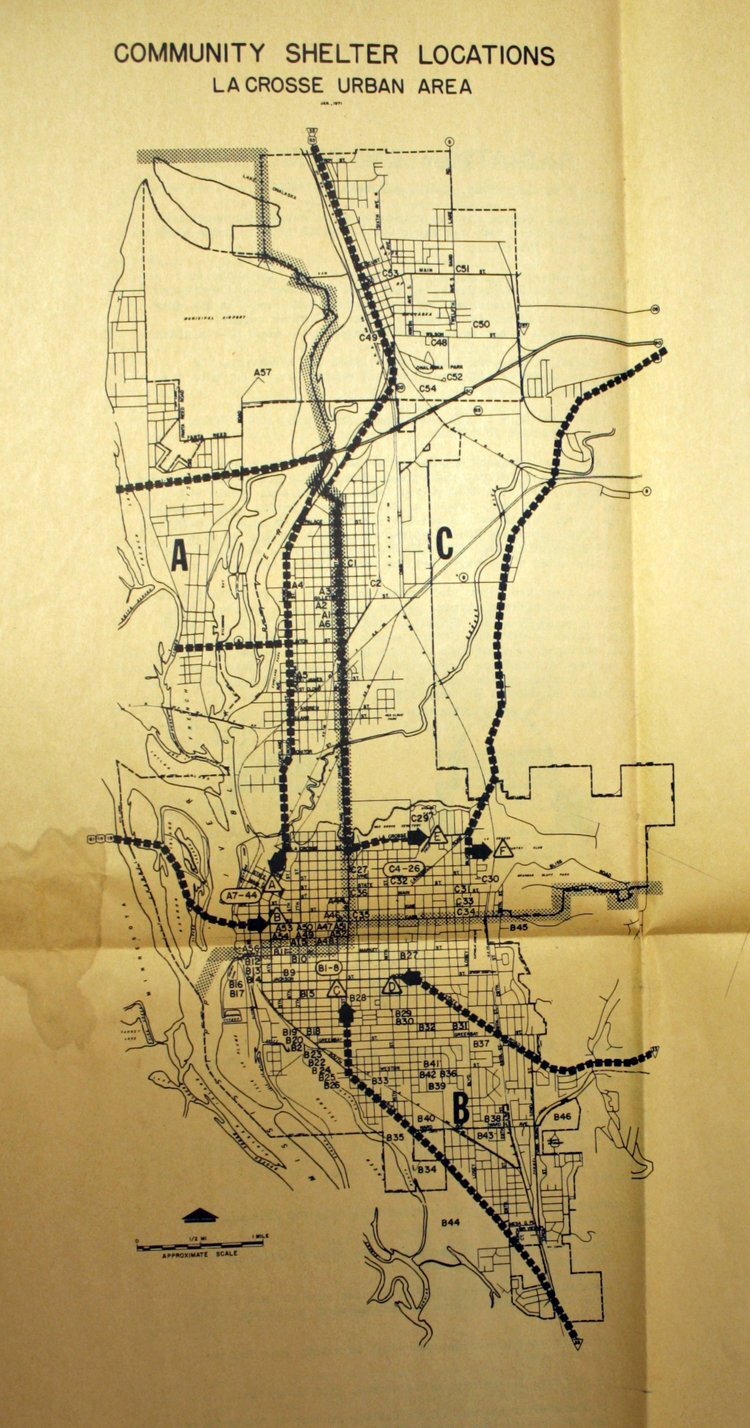

So began the “La Crosse Community Shelter Plan,” an instruction manual and map mailed to every household and business in La Crosse, Bangor, West Salem, Holmen, and Onalaska in 1971. As tensions between the United States and Soviet Union mounted in the 1950s, the Department of Defense began coordinating “civil defense” initiatives, designed to drill Americans in the arts of survival and recovery during and after a nuclear attack. If you attended school between about 1952 and 1970, there’s a good chance you watched Bert the Turtle “duck and cover” when he saw the flash of a nuclear bomb. The same Federal Civil Defense Administration that brought you Bert the Turtle also helped coordinate local civil defense plans, such as the one here.

The instructions assured city residents that “an enemy attack on the United States probably would be preceded by a period of international tension or crisis,” so the 3- to 5-minute siren – similar to our tornado sirens now – most likely would not take anyone by surprise. Once you heard it, you were to move calmly but quickly to the nearest fallout shelter. “Fallout” was the government’s term for the radioactive particles that would fall back to earth after the initial blast. The goal was to get as much stone, brick, and cement between you and the fallout as possible.

If you found yourself in the City of La Crosse when nuclear war started, you could choose from 140 fallout shelters around town; mostly churches, schools, and government buildings. If you got caught downtown, you could shelter in St. Joseph’s, the La Crosse Tribune building, or the Rivoli, among others. The University of Wisconsin-La Crosse (then Wisconsin State University) had no fewer than 23 shelters around campus. But as fans of Shaun of the Dead will know, the best place to ride out an apocalypse is a pub. Fortunately, many of La Crosse’s breweries also had fallout shelters, including 5 at G. Heileman Brewing Company alone.

So what would life be like in a fallout shelter? Stay tuned for next Saturday’s “Things that Matter.”

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune on April 25, 2015.

This object can be viewed in our online collections database by clicking here.