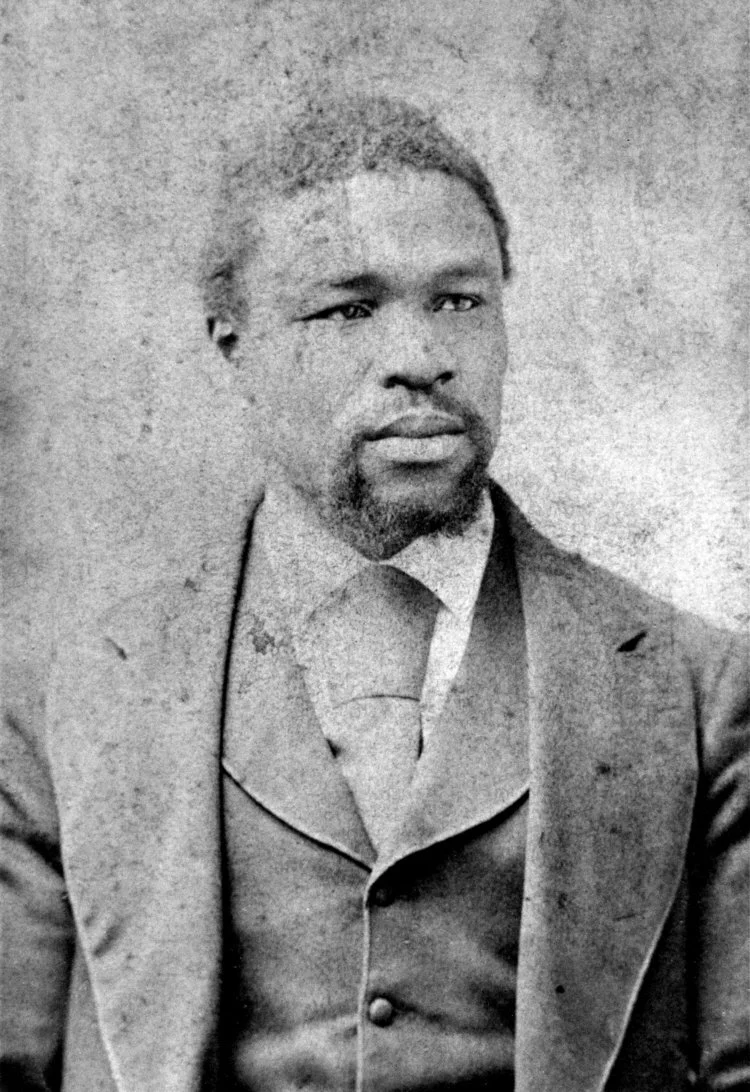

Image Courtesy of Murphy Library Special Collections at University of Wisconsin-La Crosse

Caroline C. Morris

As we prepare to celebrate the 239th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, let’s also take a moment to commemorate the 150th anniversary of “Juneteenth,” arguably the most poignant declaration of freedom in our nation’s history.

“The people of this country had gone on for years compromising with sins that were becoming so powerful that Freedom and Slavery were brought into conflict for national supremacy,” wrote the La Crosse Daily Republican on April 18, 1865. Slavery ended abruptly in the spring of 1865 at the end of the Civil War, and newly-freed men and women celebrated spontaneously all over the country as news reached them. The celebrations became an annual event, and gradually took on the name “Juneteenth,” the term used by enslaved Texans who were among the last to be emancipated in June 1865.

Roughly four million people in slave-holding states became free between 1861 and 1865. Some emancipated themselves by running to free states or Union Army encampments during the war. Union soldiers emancipated others as they fought through and occupied the Confederate states. La Crosse resident Nathan Smith, pictured above, fell into the first category. He and his wife Sarah left Tennessee around 1863, ultimately settling on a farm just north of La Crosse. The war officially ended April 9, 1865, but the surrender had ambiguous implications for the future of these formerly enslaved Americans. Freedpeople like Nathan and Sarah Smith had a relatively bright future in Wisconsin, legally speaking. They could enter into contracts to buy property, for example. The future was not as bright for the freedpeople still in the South, who had no clear legal status, and whose former owners were trying to prevent them from becoming full citizens.

The federal government had been unclear about the legal status of the freedmen and freedwomen, even during the war. President Abraham Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation,” which went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863, emancipated a portion of the enslaved men and women of the Confederate states, but stopped well short of emancipating all enslaved individuals. And as every enslaved person could attest, there was no direct link between legal words and the reality of everyday experience. What would the freedpeople’s world look like? They would no longer be property, but would they be citizens? Observers of all stripes – northern and southern, black and white, Congressmen and farmers – had widely different answers to this question in spring 1865.

Newly freed Americans took matters into their own hands by asserting their freedom and advocating for their citizenship from the earliest days of Reconstruction. Annual observances of Juneteenth celebrations were an important way for African Americans to remind one another of the hardships they had survived and to reinforce the community’s resolve to push for equal rights as citizens.

This article was originally publised in the La Crosse Tribune on June 13, 2015.