Caroline C. Morris

Catalog Number: 1970.007.01

Schools, service organizations, and churches all know how to raise money for worthy causes. Marching band needs new uniforms? Carwashes every Friday night. Time to spruce up the community garden? Bake sale. In 1898, Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church in North La Crosse made a subscription quilt.

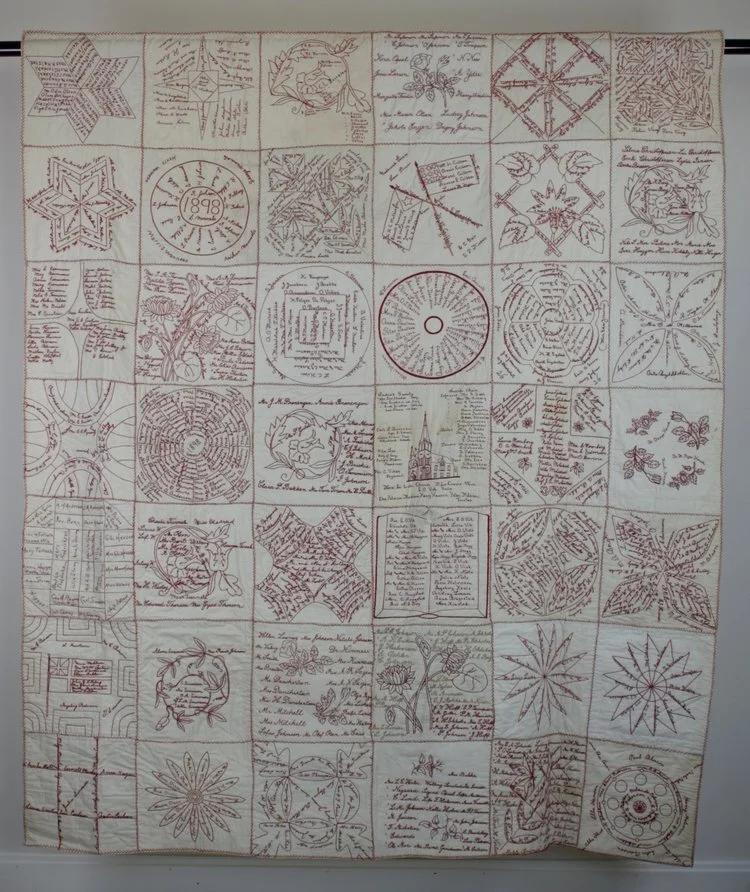

This red and white cotton quilt is comprised of 42 squares that were sewn separately and then stitched together in a style known as “potholder construction.” Each square contains many names, often arranged artistically such as in the circle above. Typically, donors paid a small sum or “subscription” – perhaps 10 cents – to have their or their loved ones’ names immortalized on the square. Look closely and the Norwegian roots of the congregation become apparent, with names such as Borressen, Nordgaard, Bakke, Pederson, and dozens of Olsens. The church would receive all signature proceeds, as well as any proceeds from the sale of the quilt at a raffle or bizarre. With hundreds of signatures, the quilt probably raised at least $40-$50, which was significant money – more than an average working man’s monthly wages at the time.

We cannot know for sure how much money the quilt raised, or its ultimate purpose. Subscription quilts of the late nineteenth century often raised money for new buildings such as schools or hospitals, for mission work, or for war. All three are likely causes for the Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation in 1898, given the church’s civic involvement and the abrupt escalation of hostiles between the Americans and the Spanish in Cuba.

The quilt was a fundraiser, but it also documented the lives and work of the women who made it. At the turn of the century, women in La Crosse were largely excluded from the most visible positions of public service; they were not pastors or mayors or high school principals. And yet, the family and social networks they cultivated and nurtured were the city’s bedrock. As Peggy Derrick, Executive Curator for the La Crosse County Historical Society explains, “these textiles remain as testaments to the engagement of women in public life even when they did not vote or often hold public office.” Derrick suggests subscription quilts such as this one honor friendships and family and social connections that might otherwise remain invisible to the historical record. The quilt is far more than a blanket; it’s an account of women’s everyday lives and work, “written” by the women of Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Church more than a century ago.

This article was originally published in the La Crosse Tribune July 18, 2015.

This object can be viewed in our online collections database by clicking here.